Matt Kelley’s short history of listening to Ike Reilly, and starting an ad agency. Originally published at OneLuckyGuitar.com as a promo for this show.

1. PUT A LITTLE LOVE IN IT

‘Salesmen and Racists’ July 31, 2001

I first heard Ike Reilly in the summer of 2001, when I lived and worked in a second floor apartment on Columbia Avenue.

A few months earlier, I had quit my job at LaBov & Beyond, where I had worked since 1996, climbing the marketing firm’s ladder, and where I was eventually invited to be a partner in the company. I was making a little-too-much money, doing high-profile marketing for wicked cool multi-national companies — selling Volkwagens! — across the country, and working with people I genuinely liked. What can I say? I was miserable.

Everyone has a story. Mine was, I bought a guitar. I bought it from Bob Dylan’s guitarist, who I ended up getting to know, and becoming friends with, and running around Nashville and the eastern half of the States with. Back in Fort Wayne, some friends and I started a band, and it turned out we were pretty good, and people wanted to see us play. I made plans to leave my job. Most remarkably of all, a girl I had been chasing for a decade — unsuccessfully — called me up and asked me if I wanted to hang out. What was happening? These were dreams. The guitar was lucky.

At the end of 2000, I went to work by myself, a freelance graphic designer, starting a business with the name “One Lucky Guitar.”

In the hot spring and summer of 2001, I sweatily worked away in the kitchen of that apartment on Columbia, listening to Teenage Fanclub and Whiskeytown and You Am I. I felt I made up for making not-nearly-enough money by enjoying what I was convinced might be the finest music collection in the city — after a rough start in high school, I had found my way in college, moving from Springsteen, to Dylan, somehow to the britpop of Blur and Pulp, with stops along the way for Lloyd Cole and, of course, Paul Westerberg and the Replacements. I loved what I loved, and looked for more of it. The newer bands I got into fit with what I was digging before, but tweaked it. Pushed it forward, a little bit. Or I’d go backwards, and hear an old record I never knew had inspired the new record that reminded me of the one in between. This was the summer of Napster, and the pained, loving, unending joy of tracking down impossible-to-find import singles of your favorite band — just to hear them perform an obscure cover of a song by a band that was about to be your new favorite band — well, that age, sadly, was sailing away. I love love loved the music, but only just a bit more than the journey to find it.

I found myself reading the web site of Minneapolis’ City Pages, in particular articles by a writer named Jim Walsh. In hindsight, I can’t remember what led me there — likely, I was looking for some kind of gossip about someone hearing something — anything — that would offer some insight on Paul Westerberg’s long silence. Like, whether he was alive or not, because I needed him. Walsh wrote with his heart on his sleeve. One day, he profiled a new artist that was taking the Twin Cities by storm. I’ve always loved hyperbole, and Walsh wrote the most hyperbolic line since Jon Landau writing about Bruce Springsteen in 1974. Walsh said, “I have waited more than 20 years to feel the way I felt when I saw The Clash perform — and finally, I feel it again. Ladies and gentlemen, Ike Reilly is here.”

I ordered his album. I was sitting sweaty in a hot kitchen, between a stove and an aging Mac tower, eating a turkey sandwich with Doritos and mustard on it, drinking a Busch Light. It was a Tuesday. IT WAS HOT. The Doritos crunched. The box fan vibrated. The birds chirped. I had turned my back on one era, and was starting another. Squinting, my life felt like a tornado.

Ike Reilly sounded like one.

From the first time I played his (unfortunately named) debut album, Salesmen and Racists, it was like I had run up to the line — the line that separates what you like and don’t like…and the closer you get to that line, the more and more acute that difference is. In that sense, the line is like a reverse spectrum. It’s not polar opposites — it’s polar the sames. I was razor-close — torn between yanking the disc out of my CD changer and whipping it out and down through the alley and aiming s quarely at the Rotweiler that had chased me down Columbia, torn between that, and starting every song over just a few seconds after it began, to re-hear what I was just hearing for the first time, again and again and again. I loved it.

The music was sharp, the words were funny and sad and poetic and glorious and raunchy and put together like an architectural wonder. Other bands were kicking the can down the road — Ike put gasoline in the can, put the can on a fence, and shot at it. The songs sounded…well, they sounded just exactly like you’d hope (or fear) a song would sound if its title was “Commie Drives a Nova” or “Hip Hop Thighs #17,” only crazier…the songs sounded like America, but not America the melting pot, because no details were lost. Nothing was without its sharpness. The only thing melting was your brain. The songs sounded like the wildest party with the biggest heart on the wildest night. I thought maybe I should walk away from this music, but I just couldn’t: it sounded just the way I felt. It was positively dangerous.

As a sidenote...

Ike was playing Birdy’s in Indianapolis that winter — my band had played Birdy’s!!! — opening for an Austin songwriter named Bob Schneider. I e-mailed a guy who had just moved from Fort Wayne to Austin, to find out what he thought of Schneider. He hated him, of course, but he liked what he heard about Reilly. (I never knew this guy in Fort Wayne, but we became penpals after this exchange, and eventually I went to visit him. Crashing at Chad and Hannah Beck’s for my first SXSW? Well, I won’t forget it.) Anyway, the night of the Birdy’s show, there was a massive snowstorm, and my girlfriend’s family talked me out of the trip. They were looking out for me.

2. GARBAGE DAY

‘Sparkle in the Finish’ Oct 12, 2004

Reilly went missing for the next three years, finally resurfacing without his major label deal, and now in a band named The Ike Reilly Assassination. I’ve always love bands — much more than “FirstName LastName and the Names” — and loved the idea of this group marketing itself as a band, and not an individual. But, my mom wasn’t going to like this. Assassination? Really? Again, right up to the line.

That said, Sparkle in the Finish had all of the flow, the flash and the bared teeth of Reilly’s debut, but shoved the boundaries out even further. The production was not quite as produced as before — it was still adventurous, but now more urgent. The songs and their subject matter were all over the place, and I found that I either had no idea what they were talking about (and pretended I did), or knew a little too much (and pretended I didn’t). The Assassination pushed the song “Whatever Happened to the Girl in Me?” to insane heights. I wasn’t sure why Ike was asking this, but I suddenly found myself asking the same question for the rest of 2004, and every few days since.

One Lucky Guitar had moved to Randallia Drive. I got married. I had written off any kind of agency freelancing — it was our clients, or no clients. I worked through the early mornings with a baby boy sleeping on my chest, listening to a track called “The Boat Song (We’re Getting Loaded).” You could feel our velocity.

As a sidenote...

The Ike Reilly Assassination was playing at Indianapolis’ Melody Inn that winter — I dreamt of being in a band that could play the Melody Inn!!! — but, again, there was a massive snowstorm, and my wife’s family talked me out of the trip. They were looking out for me. Again.

3. SUFFER FOR THE TRUST

‘Junkie Faithful’ Sept 27, 2005

Less than a year later, Reilly’s third album was released — Junkie Faithful. It was the last record I bought before boarding a plane for San Francisco, where the band I was in, The Trainhoppers, were headed to record an album. I took sleeping pills in the airport and heard the album for the first time through my headphones, the music careening in slow motion around my head like the fog was rolling off a bay we hadn’t yet seen, swirling through the aisles of the plane and into the heads of me and my bandmates, and I dreamt it would give us the brilliance and bravery and sense of risk and stupidity and yes, most of all, that it would give us the courage, the courage to create something positively dangerous.

Someday, I’ll let my kids tell me if that worked out or not.

In between Sparkle and Faithful, One Lucky Guitar had moved off Randallia, and into a small office above the nascent Avant-Garde Gallery. OLG started attracting a little attention, and we moved again, this time down the hall. There were now two of us. This was the album that was playing when we turned out the lights on one era, and turned them on in another.

As a sidenote...

A couple of years later, I would be quoted in PRINT magazine’s prestigious Regional Design Annual, reciting the lyrics from a song on Junkie Faithful, and talking about a back-to-the-wall resurgence of creativity in the Midwest, in Indiana, in Fort Wayne, in our office. "Stuck in the middle with no voice, no coast, nothing but a river and a shoreline..."

4. TODAY I DON’T

‘We Belong to the Staggering Evening’ May 8, 2007

By the time Reilly’s next record hit the streets, things were a little different at One Lucky Guitar. Our company had growns up a bit, and the days of everyone loving the spunky little kids with their design shop were over. For me, and bands, and certain purveyors of local music scene, it was a similar situation. There were some folks out there that actually hated us. In other words, we’d finally made it!

I never felt like we were on a more right course than we were that summer, and that feeling drove us, and drives us still. I needed a soundtrack for these times, our wildest times yet, and hearing Reilly’s latest was like swallowing a lit firecracker. Somehow, he had defied the odds — he’d made his best record yet (on his fourth try!) — an album that not only did everything he was great at better than he’d ever done it before, but that broke new ground and burned old ground and felt like the music that should be playing on the last, best, greatest nights of your life. It rocked, it rolled, it filled your heart — it was hilarious and terrifying and thought-provoking and charismatic and over the top. That long, hot summer, with the windows open and the sweat glistening, to sing along to this album was a most joyous kind of therapy, like laughing and crying at the same time, and like you’d never laugh or cry like that again.

As a sidenote...

The Ike Reilly Assassination was playing at Birdy’s that summer — my second band had played at Birdy’s, too!!! — and there was no snowstorm to stop us this time. The show was everything I’d imagined it would be — reckless, cathartic, funny and inspiring. The way the band worked onstage, they were chasing some kind of salvation. On the drive home, I started daydreaming of Reilly playing in Fort Wayne. Why not? A couple of our other heroes, Tim Rogers and The Avett Brothers, had come to our fair city. It seemed possible, somehow — and it was. As with Rogers and the Avetts, all we had to do was ask. It occurred to us that it was OLG’s seventh anniversary, and, well, we should have a party. We wanted to show the folks who were booking outdoor events, block parties and such, we wanted to show them that you could be ridiculously adventurous and brave in your booking, and it just might play. It just might work. The bill was some form of a Trainhoppers string band on their last legs, and Metavari learning to crawl and walk and run on their beginning legs, and then Reilly and his bandmates, pirouetting around the stage with their molotov cocktails of rock and roll. For that event, we made Lucky Seven shirts, and on the inside-back, below the neck, we printed SEVEN YEARS AND STILL NO BULLSHIT.

5. LIGHTS OUT, ANYTHING GOES

'Hard Luck Stories’ Nov. 24, 2009 / Feb. 16, 2010

It was immediately apparent to me that we should try to get the Assassination back to Fort Wayne as part of the Lucky Ten series of shows. Unbelievably, One Lucky Guitar is celebrating its 10th year of existence. As OLG client John Prine once sang, “It’s a big ol’ goofy world”…and I’m not sure there’s much out there that’s more true than that statement. We’ve grown to a team of nine, and I get to work with eight seriously amazing people, great partners, and a roster of amazing clients.

At the end of 2009, Ike released his excellent Hard Luck Stories as a digital download — surrounded by ridiculously fantastic podcasts — just as all the music publications and blogs and “drooling fanatics” were writing about the decade that was. It occurred to me that Reilly had kicked off, and wrapped up, the decade with one of the most impressive five-for-fives in music history — ever-growing, ever-evolving, full of conviction, forever restless and endlessly hungry. His musical spirit reminded me of OLG, in a way, once again.

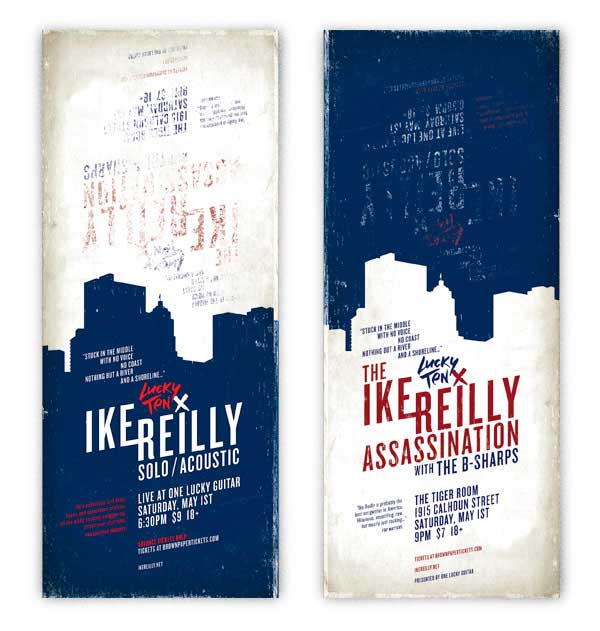

This Saturday, May 1st, Ike Reilly plays two shows in Fort Wayne — first, solo in our office (our office!!!), and then later that same night at The Tiger Room, with the full Assassination and openers The B-Sharps (on their last legs). It’s hard to describe what this means to me, or how, 10 years later, you can still be so damn surprised and amused and blown away by what might happen when the best and bravest ideas get mixed with a generous, undeniable helping of willpower, and where quitting is not an option. Trying to find context for this show, I find myself thinking about how The Who played in Fort Wayne in 1967, at The Swingin’ Gate, a little club that’s now a parking lot on Berry Street. It’s been 43 years since we last saw something so positively dangerous.